Corrupted Blood Incident, the World of Warcraft (WoW) virus from which South Kiosk’s summer exhibition takes its title, infected the online game when the Zul’Gurub dungeon was introduced in 2005. In this raid, or mission, players were given the chance to take on Hakkar the Soulflayer, a fearsome creature capable of casting a contagious hit-point draining spell. Its effects were supposed to be contained within the dungeon, but due to a programming oversight, it escaped, spreading throughout the game, rapidly laying waste to thousands.

Though Corrupt Blood Incident (South Kiosk, London, 2017) is based on an epidemic from the virtual world, the visitor finds the gallery blighted by a decidedly real contamination. The audio tracks of the various video works produce a cacophony of noise – a kind of sonic contagion – in the midst of which a siren sounds, signalling, the visitor imagines, the release of some lethal toxin. To the immediate left of the entrance stands Jamie Shovlin’s Jamestown Sign (2013). “Jamestown […] A real nice place to be” reads the large red American road sign, haphazardly flipped on its side, indicating a panicked mass-exodus of a once pleasant town, like the WoW gamers, who hurriedly abandoned populated cities to survive. Equally disturbing, Daniel Shanken’s series of computer-designed collages entitled OBLIQUE TRANSMISSIONS (2017) pictures a collection of plants of the most colourful and aggressively spiky kind, conjuring a biosphere intoxicated by a radioactive spill. If the danger posed by South Kiosk’s gallery seems so far fanciful, the frames in which Shanken’s works are presented prove otherwise. Charged with an electrical current, they crackle and spark, threatening to shock the passing viewer.

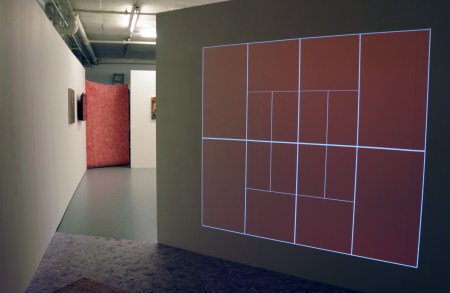

Corrupt Blood Incident (2017), Installation view

Selachimorpha (2016), Joey Holder

Like electricity, pathogens have the ability to breech the skin with relatively little resistance but unlike a brief shock, a virus determines to stay in the body. Being colonised by an alien presence, the body is disembodied from within, made a stranger unto itself. Alzbeta Jaresova’s series of graphite drawings entitled Position XXI, XXV, XXIII (2015-17) depicts various hands, obscured to their owners’ eyes by opaque planes (though sheets of glass allow them to see a reflected image, an uncanny trace of corporality). The drawings invoke the rubber hand illusion, whereby a person can develop a sense of touch for an artificial hand if they cannot see their own. They also refer to the neural disjunct between sight and touch precipitated by technologies such as virtual reality goggles and, more generally, the way computer-generated environments disembody us from reality.

The exhibition leads to the question, can gamers feel for the bodies of the avatars they adopt? Two artists in the exhibition, Tom Kobialka and Angela Washko, explore corporality and sexual pleasure in gaming. Kobialka’s video work Vibrant Breath (2016) presents a simulation of a dungeon-type space in which a character from the game Dark Souls III is tightly tied, similar to Shibari, the Japanese art of bondage. From the audio, straining and panting can be heard. A man’s breathy voice says, “More intimacy in the digital […] yeah, that’s nice”. The first thought is that the man is masturbating to the sight of the struggling beast but then the viewer notices that the man’s grunts coincide with the simulation’s movements, indicating the voyeur imagines he is the bound creature. Angela Washko’s Playing a Girl (2013) engages with similar ideas of vicarious sexual pleasure. The video is an extension of the artist’s activity as the founder of the Gender Sensitivity and Behavioural Awareness Council for WoW. Washko investigates why so many male WoW players adopt female avatars; the video features an in-game recording of her interactions with such players. In one chat-message exchange a player remarks, “I’d rather look at a girl’s butt all day […] it would be gay to look at a guy’s”. As Washko wrote in Creative Time, men play women not to empathise with their experiences; “WoW merely offers men another opportunity to control an objectified, simulated female body”. Like Kobialka’s video, Washko’s work shows that simulated avatars allow gamers to be the object and subject of their own desires – a deviant narcissism facilitated by virtuality.

Corrupt Blood Incident (2017), Installation view

As multi-user environments, WoW and other virtual worlds have the potential to be highly social, democratic spaces but they are often inhabited in deeply solipsistic ways. Significant aspects of identity – not just desire – are constructed in digital environments, which presents various potential existential crises. What if your avatar is destroyed by a virus, like the one that blighted WoW; or what if your avatar is hacked? Kobialka’s Pastebin.dump (2016) explores the second of the two calamities. The work presents a list of leaked gamer usernames and passwords, which was transcribed by a robot onto the whiteboard shown in the gallery. What was uniquely individual and private becomes public property.

The third and final identity crisis posed by virtuality is the misinformation that circulates the internet today. Joey Holder’s Selachimorpha (2016) takes its title from the scientific classification for sharks; the video installation examines the conspiracy theories surrounding an odd scene in Steven Spielberg’s 1975 movie Jaws in which a shooting star streams across the sky. While some say the star was added in post-production, others insist it’s a UFO. Indeed, comets, like sharks, have always been rich sources of mythology. As Slavoj Žižek comments in his filmic treatise, The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology (2012), the shark in Jaws has been interpreted as many different symbols of fear: one of natural disasters, or of immigration or even big capital. Which is right? None and all of them, claims Žižek. “Ordinary people […] have a multitude of fears, […] the function of the shark is to unite all these fears”, reducing a complex set of fears into a single, tangible (crucially destructible) entity. Similarly, the idea that the Rothschild family controls the world economy offers a facile explanation of global capital exchange. But the cost of simplification is factuality. As Pepe the Frog – a symbol for Donald Trump – appears at the climax of Holder’s film, the viewer is reminded that in the so-called post-truth era reality is beyond mattering. As South Kiosk’s engrossing and explorative exhibition shows, as humans construct ever more elaborate virtual identities, the real world becomes increasingly irrelevant. But if the virus that plagued WoW in 2005 teaches us anything, it is that lives lived in virtuality can be snuffed out at any moment.

Henry Broome

Henry is freelance art writer based in London. He is especially interested in technology, the future and the slippage between objecthood and subjecthood.

Featured image: Jamestown Sign (2013), Jamie Shovlin

Pingback: Review: Corrupt Blood Incident – Henry Broome: Writing