In a time where the internet has redefined our perception of art and curatorial practice, it is no wonder that online exhibitions and residencies are becoming more and more part of contemporary culture. One of them is the online residency x-temporary.org, a platform founded by Marenka Krasomil to work together with artists in a digital space, to present ideas, and develop artistic concepts. One characteristic of x-temporary.org is that the platform has no archive — a way of withdrawing from constant and permanent accessibility of the internet. As the current resident, Johannesburg-based artist Carly Whitaker, who describes herself as a digital practitioner, is performing Bae Magick during the month of April. As a well composed combination of cosmic kitchy images and the more than familiar surfaces of our daily used devices, Bae Magick is casting magick spells and performs rituals in relation to the phases of the moon. In an interview with Elena Frickmann, Carly Whitaker talks about love in and through the digital, the influence of new media on our relationships and creative practice online.

Elena Frickmann: Before we start talking about your current project, can you explain what the term ‘bae’ means to you?

Carly Whitaker: Bae stands for before anyone else. It’s the person who shares their Apple Music login deets with you so you access the playlists they made especially for you, they give you their password when you need to quickly Google something and your phone is too far away. Bae is the person you tag in your status update and always features in your profile picture. It’s the person who doesn’t mind helping you take the cutest selfie and always checks your Snapchats. Bae is the person who always tags you in funny memes to cheer you up and sends you DMs of silly things other people have done online. They also always text back. You get different types of baes too; pseudo baes, temp baes and long-term baes.

EF: Bae Magick, as well as other projects of yours such as EMOJIKINDALOVE from 2016, revolves around the topic of love. Do you think it became easier for the generation of the so-called ‘digital natives’ to find love?

CW: I think its accessibility seems to be easier. Apps and online dating sites make it appear easier, but I don’t think that it actually is in reality. I think the digital medium makes ‘finding love’ far more complex and sometimes disposable. It’s easy to swipe right, start messaging and then ghost on someone. Being in a relationship requires work and effort, what the digital medium makes easy is to form a ‘connection’ but anything beyond that still requires more than an interaction with your phone. In my work, I’m interested in how we form these connections, try and make them work through our phones and different apps etc. EMOJIKINDALOVE looks at how we define our emotions and equate different stages of relationships to different emojis. As an aesthetic, they start to reflect our love lives and relationship through their repetition and frequency in text messages. All of the feels for you (2016) looks at the initial stage of falling for someone and how your emotions can build and grow and expectations change or are challenged when negotiating a new relationship over texts.

EF: When I saw your ‘cleansing ritual’, deleting a text message, a number, the digital traces of someone, it reminded me of myself, acting like this when a love story ends. To be honest: it doesn’t help much to heal the pain, but this leads my thoughts to archives and memories. Is this something you think about in your practice?

CW: Definitely. These devices also capture a lot of our relationships. The archive that we develop on our phones is super interesting – it acts like a personal historical narrative that we can access if we want, at any time, provided you are online. I’m going to be looking at that a lot over the next few spells I think. I think it’s not so much about the pain of a break up or about wanting to erase that relationship, but the space that an old love can take up both technically and emotionally. The words that scroll across the screen “new phone, who dis?” reflect that. Having contact details, messages and photos still on your phone – so accessible – doesn’t allow you to always move on. Some relationships that end need that space in order to be final, but some can linger. This can be super difficult and almost like the final step in accepting that something has ended. By deleting these traces you can make room for new relationships and new digital spells. I think it depends on you and the relationship or the amount of space you have on your phone.

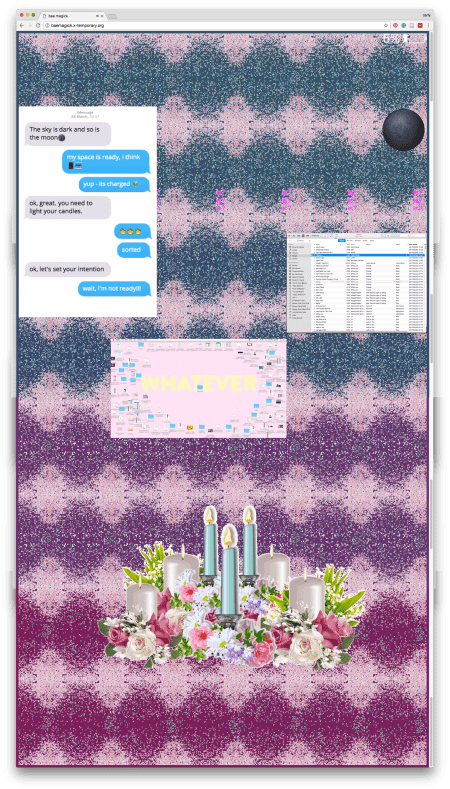

The new moon brings new energy; it is a time for new beginnings, for starting anew and for self-improvement and cleansing of spaces and ridding of bad or negative events. The spells cast during the first week saw a cleaning of digital spaces and starting afresh. Performing digital magick is about cleansing your digital space, cleaning your phone and cleaning your desktop, starting anew… Enabling your battery to be fully charged, ready for the coming spells and energy of the moon.

New Moon (2017), Bae Magick, Carly Whitaker

EF: The language in Bae Magick is very esoteric, mentioning words like ‘magick’, ‘ritual’, ‘energy’, ‘the moon’. This stands in contrast to its digital aesthetics. How do you link these two spheres?

CW: Those spheres are in contrast but somehow make sense to my practice. If you look closely at the digital medium, it is magical and I love that about it. I love that you can play and imagine ways of seeing, behaving, fictions and creating in it. There is an energy online, a spirituality, which you can choose to grasp or engage with or not. In a similar way, you can choose to focus your own energy, the energy of the moon, and use it for strength, change or affect. I love how the digital medium – aesthetically and formally – echoes and reflects how we behave in reality. We construct and create spells in order to capture energy, in the same way we can construct and create our lives online. There is something ritualistic about the online medium, especially the mobile phone. We carry them with us at all time; we check them repeatedly and ritualistically. I personally check Instagram before I go to bed and when I wake up first thing. We track our lives on our phones, or it tracks them for us, and tells us what to do and when etc. These rituals are focused on the content and a relationship forms with this device. We construct and imagine all sorts of fictions for ourselves and the world within these devices which hold so much power.

EF: Being the current artist in residence on x-temporary.org is not your first encounter with online exhibitions and platforms. Can you tell me a bit more about your experience with it and which importance it has for you?

CW: Sure, I think the digital medium online is exciting and comes with a certain amount of freedom with it – seemingly. I run an online residency programme called Floating Reverie where I act as the curator/programmer. It happens once a month for two weeks. Artists are invited to participate and respond to the brief. My creative practice, my curating and research are all intertwined at the moment. I am interested in how curatorial methods are implemented in the online medium and post-internet work as a form of creative practice and have the ability to create new frameworks for creative practice and new dialogues outside of traditional artistic structures.

EF: Not only the accessibility of love seems easier through new and social media, but also the visibility and accessibility of art. How do you see this process? Especially through the eyes of someone who is not necessarily based in one of the typical contemporary art locations like New York, London or Berlin.

CW: I think that the accessibility, or visibility, of art is complex and could be equated to love online and who has access to those channels. Saying that though, the online medium is not the only channel. You can find love if you’re not online and you can make art or see art if you’re not online, but there is definitely a way that we consume art online that has changed the way we see art or whose art is seen. I think that the subject matter that I work with speaks to a collective sentiment that many people are extremely familiar with and that can also influence the accessibility of the art. Art that exists through the digital medium, through the internet, allows for a certain amount of accessibility. Art online or offline is not always that accessible literally or conceptually for a lot of people in a variety of locations. If you replace the word art with love this may read differently.

Elena Frickmann

Elena Frickmann is a curator, art historian and art critic, currently based in Freiburg, Germany. She studied linguistics, literature and art history in Trier and Florence and graduated from Goethe-Universität and Städelschule Frankfurt am Main with an MA in curatorial studies focused on contem-porary art. Her curatorial projects include several group exhibitions in Madrid and Frankfurt am Main. She has worked for Städel Museum, Galerie Parisa Kind and her texts have been published in various edited volumes and exhibition catalogues, such as Hélio Oiticica: Curating the Penetráveis (transcript, 2016) and Ich sehe wunderbare Dinge – 100 Jahre Sammlungen der Goethe Universität (Hatje Cantz, 2014). Currently working as assistant curator at the Museum für Neue Kunst, she is researching on topics of contemporary forms of collecting, geopolitics and the influence of the geographical location on perception.

Carly Whitaker is resident on x-temporary.org for the month of April.